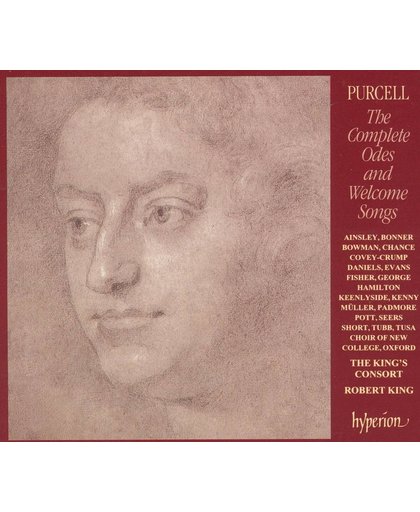

Purcell: The Complete Odes and Welcome Songs / Robert King

Available at:

From between 1680 and 1695 twenty-four of Purcell’s Odes and Welcome Songs survive: four celebrate St Cecilia’s day, six are for the welcome of royalty, three are for the birthday of King James II, six celebrate the birthdays of Queen Mary from 1689 to 1694, and the remainder are ‘one-offs’ for a royal wedding, the Yorkshire Feast, the birthday of the Duke of Gloucester, the Centenary of Trinity College Dublin, and one for a performance ‘at Mr Maidwell’s School’. Of these twenty-four only a handful receive regular performances today, and the remainder, full of wonderfully inventive music, are usually and unjustly ignored. Besides its musical and historical importance as the first recording of all Purcell’s Odes and Welcome Songs, the eight discs in The King’s Consort’s series on Hyperion have an added interest for the scholar as the Odes cover almost all the period of Purcell’s activity as an established composer; his first Ode, for the welcome of Charles II, dates from 1680, and his last (that for the six-year-old Duke of Gloucester) was written just a few months before the composer’s untimely death in 1695.

Like the forty or so plays for which Purcell provided incidental music and songs, many of the libretti for the Odes are undistinguished. These texts accounted, in part at least, for the Odes’ neglect in the twentieth century. Purcell himself appears to have been less concerned by the texts he was given, consistently turning out music of astonishing imagination and high quality and frequently reserving his finest music for some of the least distinguished words. Seventeenth century audiences were perhaps not so preoccupied by texts as their modern counterparts—Purcell’s ravishing music must have been more than adequate compensation for poor poetry—and John Dryden, translating Virgil in 1697 backs this up: ‘The tune I still retain, but not the words.’ There was in any case a conventionally obsequious attitude to royalty, and Purcell’s music always wins, as the satirist Thomas Brown summed up:

For where the Author’s scanty words have failed,

Your happier Graces, Purcell, have prevailed.

Records of payments made to instrumentalists and singers for special occasions show the forces (and indeed the actual venues) utilized to have been surprisingly small. The ‘vingt-quatre violons’, modelled on the French version, were almost never at that strength by the 1690s, with the English musical establishment firmly in decline following the royal realization that music did not make money. All but the largest of Purcell’s Odes (notably Come ye sons of Art and Hail! bright Cecilia) seem to have been intended for performance by up to a dozen instrumentalists and a double quartet of singers, who between them covered all the solos and joined forces for the choruses. We believe therefore that the ensemble recorded here parallels the number of performers that took part in seventeenth-century performances.

Purcell: The Complete Odes and Welcome Songs / Robert King

From between 1680 and 1695 twenty-four of Purcell’s Odes and Welcome Songs survive: four celebrate St Cecilia’s day, six are for the welcome of royalty, three are for the birthday of King James II, six celebrate the birthdays of Queen Mary from 1689 to 1694, and the remainder are ‘one-offs’ for a royal wedding, the Yorkshire Feast, the birthday of the Duke of Gloucester, the Centenary of Trinity College Dublin, and one for a performance ‘at Mr Maidwell’s School’. Of these twenty-four only a handful receive regular performances today, and the remainder, full of wonderfully inventive music, are usually and unjustly ignored. Besides its musical and historical importance as the first recording of all Purcell’s Odes and Welcome Songs, the eight discs in The King’s Consort’s series on Hyperion have an added interest for the scholar as the Odes cover almost all the period of Purcell’s activity as an established composer; his first Ode, for the welcome of Charles II, dates from 1680, and his last (that for the six-year-old Duke of Gloucester) was written just a few months before the composer’s untimely death in 1695.<br /><br />Like the forty or so plays for which Purcell provided incidental music and songs, many of the libretti for the Odes are undistinguished. These texts accounted, in part at least, for the Odes’ neglect in the twentieth century. Purcell himself appears to have been less concerned by the texts he was given, consistently turning out music of astonishing imagination and high quality and frequently reserving his finest music for some of the least distinguished words. Seventeenth century audiences were perhaps not so preoccupied by texts as their modern counterparts—Purcell’s ravishing music must have been more than adequate compensation for poor poetry—and John Dryden, translating Virgil in 1697 backs this up: ‘The tune I still retain, but not the words.’ There was in any case a conventionally obsequious attitude to royalty, and Purcell’s music always wins, as the satirist Thomas Brown summed up:<br /><br /> For where the Author’s scanty words have failed,<br /> Your happier Graces, Purcell, have prevailed.<br /><br />Records of payments made to instrumentalists and singers for special occasions show the forces (and indeed the actual venues) utilized to have been surprisingly small. The ‘vingt-quatre violons’, modelled on the French version, were almost never at that strength by the 1690s, with the English musical establishment firmly in decline following the royal realization that music did not make money. All but the largest of Purcell’s Odes (notably Come ye sons of Art and Hail! bright Cecilia) seem to have been intended for performance by up to a dozen instrumentalists and a double quartet of singers, who between them covered all the solos and joined forces for the choruses. We believe therefore that the ensemble recorded here parallels the number of performers that took part in seventeenth-century performances.